Flexible CO2 Capture and Storage in a Transactive Energy and Carbon Market

By Mingyu Yan, Hamid Arastoopour and Mohammad Shahidehpour

The excessive CO2 emission has resulted in major challenges for the development of a sustainable human society. CO2 emissions contribute to the climate change and global warming, and the recurrent of more intense natural disasters (e.g., hurricanes, floods, fires, ice storms). Fossil-fueled power generation contributes to over 40% of hazardous emissions globally, and proper mitigations of CO2 emissions can intensify the decarbonization of our communities.

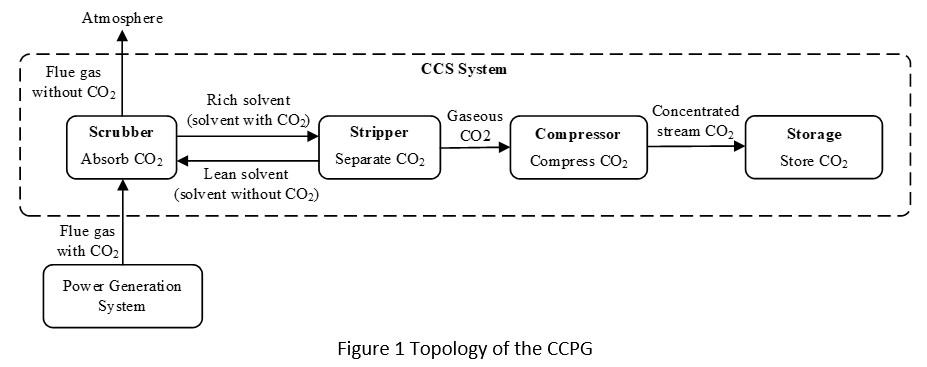

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology is one of the most promising options in reducing the CO2 vented by power generators, which can evolve into CO2-captured power generators (CCPGs). So, once a power generation system combusts the fossil fuel and vents the flue gas, the CCS system would capture the CO2 emission from the vented flue gas and store the CO2. The use of CCS will not only reduce the CO2 emission but also enhance the operational flexibility of conventional fossil-fueled generators. Figure 1 shows the commercial CCS system which consists of scrubber, stripper, compressor, and storage. The scrubber would absorb the CO2 in the vented flue gas by using the solvent. The stripper separates the CO2 from the solvent, and further delivers the CO2 to the compressor. The compressor compresses the gaseous CO2 into concentrated stream CO2, while the storage is applied to store the concentrated stream CO2. In a near future, a higher efficient CO2 absorption based on solid sorbent will be available which will make the CCS system more economically feasible.

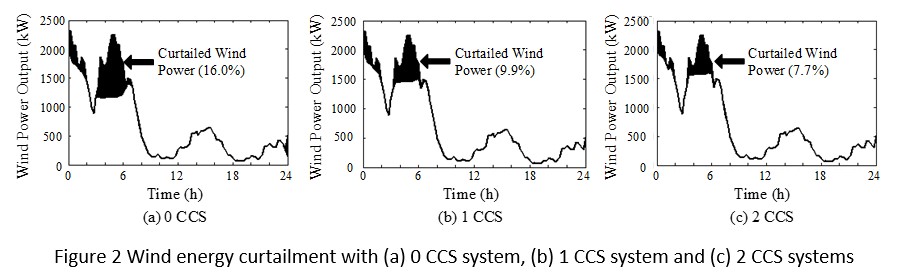

In CCPGs, CCS and power generation systems work independently. The CCS system, which consumes a small portion of the power produced by the power generation system, can be applied to reduce the peak load and accommodate the variability of renewable energy resources in the power generation system. The CCS system can be charged at off-peak hours to capture CO2 like a battery and release power to reduce the load at peak hours (i.e., peak load shifting). Figure 2 shows the wind power curtailment with and without the CCS system, where the CCS can significantly reduce the wind curtailment. As the number of CCS systems is increased from 0 to 2, the wind power curtailment is decreased from 16.0% to 7.7%. However, the CCS system could be costly, add to the operational complexity of conventional fossil-fueled generators, and reduce the generators’ efficiency as it consumes some of the generated power. Such drawbacks are major obstacles to the utilization of the CCS system and widespread deployment of CCPGs. To counter some of these drawbacks, we propose a transactive market for energy and carbon, which can incentivize additional investments in CCS facilities.

Transactive Energy and Carbon Market for Mitigating the CO2 Emission:

Transactive energy market was proposed for trading energy among microgrids (MGs), and struck a balance of local energy production and consumption. In a transactive energy market, participating MGs with their specific energy production and consumption profiles can use market signals for exchanging energy services in a power distribution network. The energy trading can incentivize MGs to full use of local energy productions to provide affordable energy to their respective customers. The transactive energy market can promote the use of demand response when the available energy resources cannot fully supply local loads and the imported grid power is expensive. Accordingly, MGs can shift non-critical loads to maintain the local power balance at the lowest cost in a transactive energy market.

A similar idea is applicable to a transactive energy and carbon market where a carbon cap-and-trade carbon emission trading market is considered to reduce CO2 emissions. In this market, each MG uses its carbon right, which is the right to vent a limited amount of CO2, and trade both energy and carbon to maximize its payoff. If an MG intends to vent more CO2 than its carbon right for producing energy, the MG can purchase additional carbon right from its peers or reduce its power generation to satisfy its carbon right obligation. The transactive energy and carbon market will accordingly incentivize MGs to perform a cost/benefit analysis for the installation of the CCS system and thus reducing their CO2 emission.

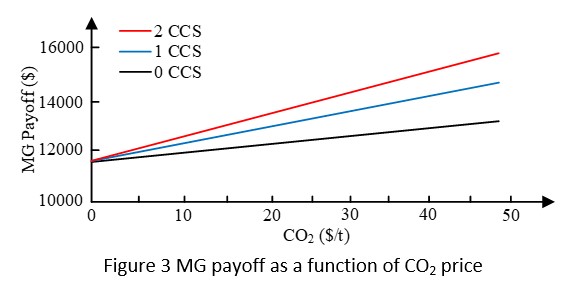

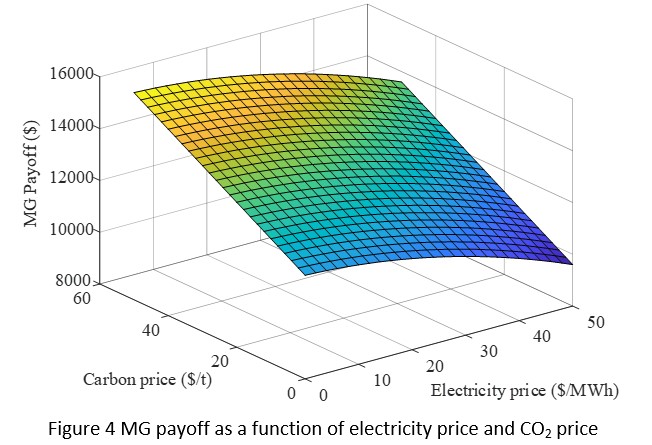

Figure 3 shows the MG payoff as a function of the CO2 price. As the CO2 price increases, MGs can gain more by selling more carbon right. Therefore, the MG payoff increases as the CO2 price is increased. Since the CCS system can capture the CO2, MGs equipped with the CCS system can sell more carbon right and enhance their payoffs. Let’s assume that 2 CCS systems are installed. Figure 4 shows the MG payoffs as a function of carbon and electricity prices. The CCS system can capture CO2 which can be traded and increase the MG payoff as the CO2 price is increased. As electricity prices increase, MGs which would have to purchase energy from the power grid will reduce their payoffs.

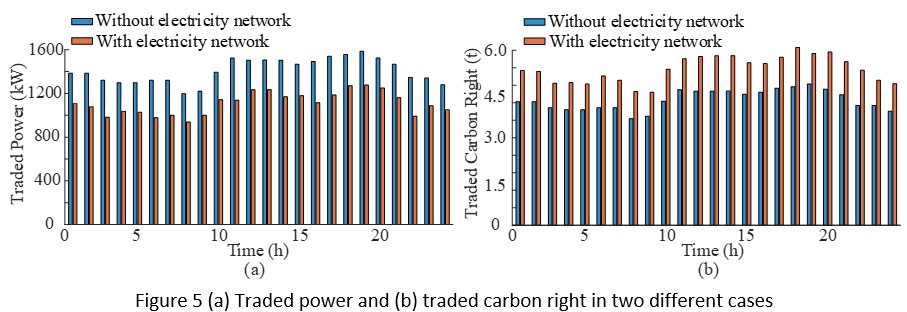

Figure 5 shows the traded carbon rights and power with and without electricity network constraints. The MGs’ total payoffs are $ 14,316 and $ 11,629, without and with electricity networks, respectively. Here, network constraints would limit MG trades and lower the total payoff by 19%. In addition, since the electricity network could restrict the trades among MGs, the MGs would have to balance their load by utilizing their own distributed energy resources (e.g., microturbines). In such cases, MGs would vent more CO2 and could be in need of purchasing additional carbon rights. Accordingly, as shown in Figure 5(b), carbon right trades could be increased considering the electricity network.

This article edited by Vigna Kumaran

For a downloadable copy of the January 2021 eNewsletter which includes this article, please visit the IEEE Smart Grid Resource Center.

To have the Bulletin delivered monthly to your inbox, join the IEEE Smart Grid Community.

Past Issues

To view archived articles, and issues, which deliver rich insight into the forces shaping the future of the smart grid. Older Bulletins (formerly eNewsletter) can be found here. To download full issues, visit the publications section of the IEEE Smart Grid Resource Center.